Two Inheritances: My Family History

“Will Mama’s Irish genes save me? How many times have I thought about changing my name?” - a quote from Chapter Two of “Surfing The Interstates”

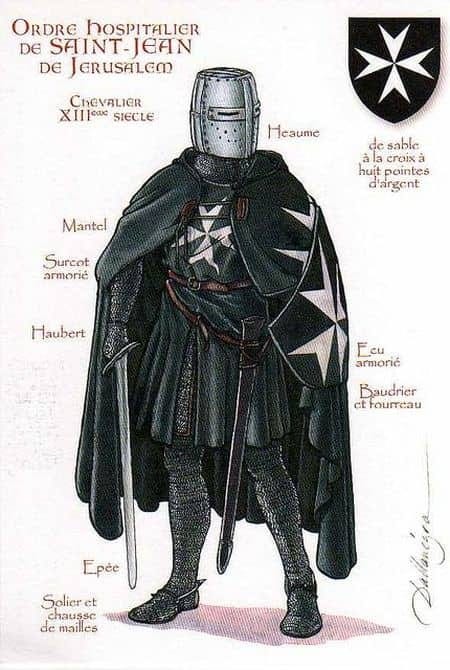

My birth in 1952 brought together two vastly different family traditions. The Saint Phalle lineage traced back to 1240, to the very first André de Saint Phalle, known as Andre I—a knight of the Order of Saint-John of Jerusalem.

The family motto—”My cross binds me to God, my sword to the King”—reflects centuries of military and religious service.