Growing Around Damage

A 1973 hitchhiking memoir that maps the architecture of American male loneliness

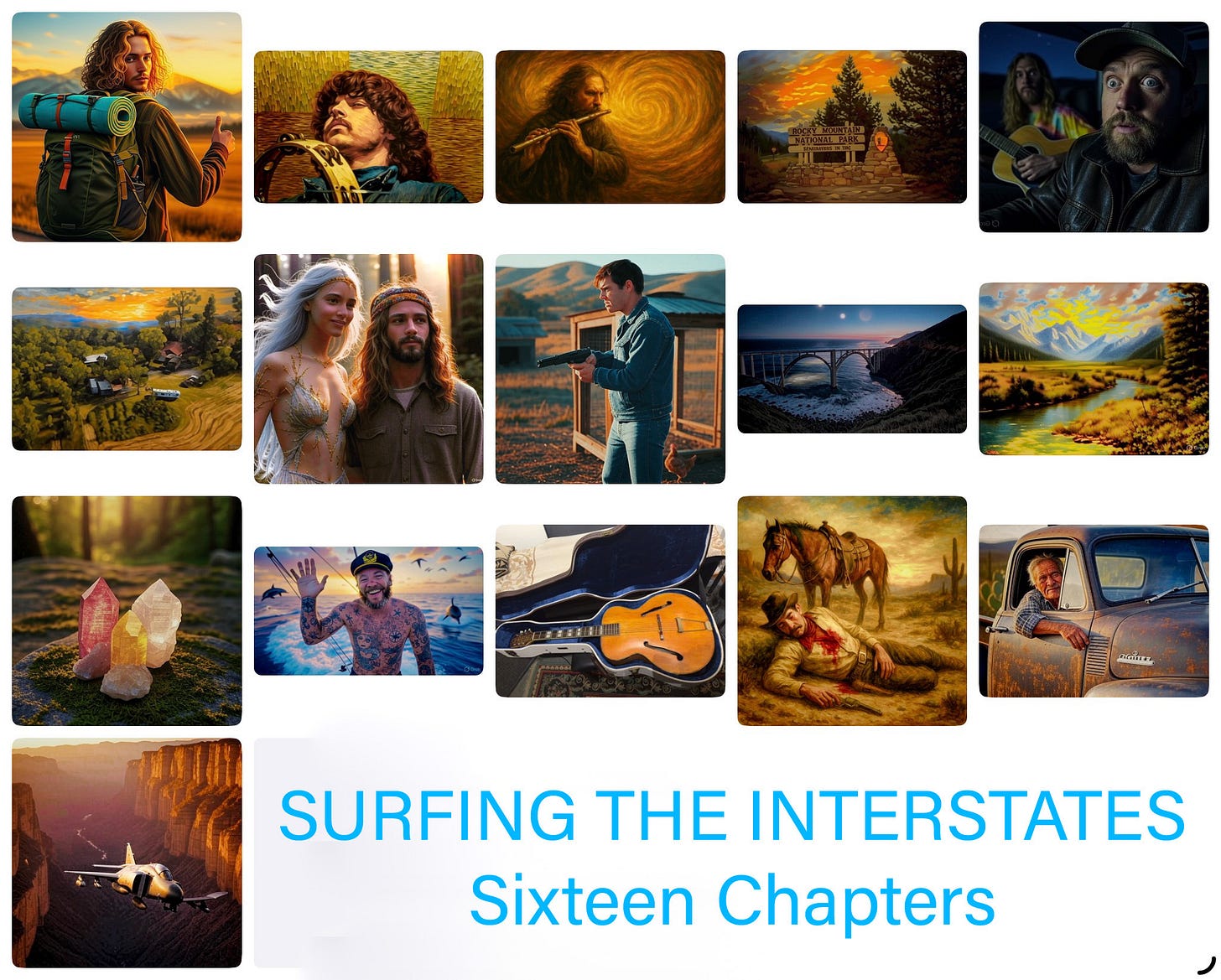

“Surfing the Interstates” chronicles a young man’s raw, psychedelic hitchhiking odyssey across 1970s America, blending vivid encounters, Grateful Dead fandom, and spiritual awakenings into a memoir that holds its own against the genre’s touchstones. But beneath the road narrative lies something more urgent: a document of how a particular kind of American man—smart, sensitive, raised in emotional isolation—learns to stop running.

Subscribe to read · Download PDF

The memoir opens with André, a restless twenty-one-year-old, fleeing a fracturing family in New York. Burdened by paternal expectations, Catholic guilt, and unprocessed trauma from witnessing domestic violence, he pockets his mother’s hidden cash, slings his Harmony guitar, and thumbs west toward California—chasing Kerouac myths, Grateful Dead salvation, and freedom from his controlling father. He is raw, impulsive, and spiritually adrift.

Encounters unfold episodically as the road chisels him: Vietnam vets dispensing hard-won wisdom, a flute virtuoso steering with his knees, mountain communes pulsing with free love and folk tunes, a troubled friend whose paranoia deepens with each visit. The prose crackles with sensory immediacy—Colombian gold smoke curling through Pennsylvania woods, canyon walls breathing during a desert fast, Jerry Garcia cradling the hero’s guitar like a talisman.

The Truncated Redwood

At the heart of the book stands an image easy to miss on first reading: a damaged tree, its lightning-struck crown sprouting new growth sideways. That tree becomes the book’s quiet thesis: you grow around damage, not through it.

The connection becomes explicit when André links it to his own body—a compound fracture at six, growth plates destroyed by infection, his father reading “The Little Engine That Could” as if willpower could heal bone. Later, sorted into the lowest athletic tier at Exeter because he couldn’t climb ropes fast enough. The invisible disability. The body that betrayed him early and taught him that adaptation isn’t failure—it’s survival.

This isn’t inspiration-speak. It’s a hard-won understanding that some damage doesn’t heal, doesn’t build character, doesn’t make you stronger. You just learn to grow sideways.

The Architecture of Male Loneliness

Some readers may frame the book’s challenges as cultural drift—Gen Z swiping past analog risks. But that misses what makes the material timeless. The hitchhiking is just the vehicle. What the memoir actually documents is the architecture of male loneliness in America.

A dream sequence makes this explicit: an African village with its mud streets, its dancing, its continuous community. André writes:

“In the village, everyone grows up together. Boys and girls playing in the same mud. Learning each other’s faces, fears, dreams. Not separated at thirteen. Not sent to stone towers where girls existed only as theory.”

That’s not 1973 nostalgia. That’s a diagnosis that applies to every generation of American men raised in emotional isolation and then expected to suddenly know how to love. The boarding schools, the all-boys education, the seven moves before André turned eight—these created the specific wound he carries. But the wound itself is universal: never learning the dailiness that transforms bodies into people.

Kerouac’s Shadow

The comparison to “On the Road” is inevitable and instructive. Both chronicle hitchhiking quests for transcendence: Sal Paradise and Dean Moriarty chase bebop-fueled epiphanies across 1940s America; André surfs interstates amid peyote visions and vet wisdom. Kerouac’s breathless prose mythologizes aimless jazz joyrides; “Surfing the Interstates” grounds similar freedom in era-specific grit.

Where Kerouac’s stylistic jazz riffs blur into self-indulgent haze and his characters remain archetypal sketches, this memoir snaps tighter. André’s evolution carries palpable psychological weight absent in Kerouac’s saintly hedonists. Kerouac mythologizes; André witnesses.

For character arc and verisimilitude, “Surfing the Interstates” earns its place as worthy successor—perhaps superior in craft, if not in cultural moment.

Why It Still Matters

Today’s readers navigate gig economies and GPS-tracked Ubers, not thumbing into Trans Ams amid post-Vietnam fallout. Hitchhiking’s romance died with serial killer panics and privatized highways. The memoir’s unfiltered questing—family cash heists, casual acid sacraments, road encounters without contemporary anxieties—clashes with sensibilities shaped by liability culture and content warnings.

Yet the book offers precisely the antidote to scripted lives. And its endurance won’t rest on period details. The wound it describes—male loneliness, emotional exile, the inability to stay—is still being inflicted on boys right now. The boarding schools may have different names, but the architecture of isolation persists. Young men raised on screens instead of stone towers still arrive at adulthood wondering why intimacy feels like a foreign language.

The book deserves readers. Not because it’s a period piece, but because the truncated redwood still teaches those willing to see: you grow around damage, not through it. And sometimes the crooked branches reach higher than the straight ones ever could.

SURFING THE INTERSTATES: 1973 Hitchhiking Memoir

Subscribe to read · Download PDF

A longer critical analysis—with full spoilers—will follow for those who’ve completed the journey.